Understanding Hamas

Navigating the Islamic Resistance Movement

﷽

Amidst the genocidal bombardments currently being perpetrated by the nebulously named Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) against both militants and civilians in Gaza, many western observers are, seemingly, being introduced to the Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) and its subsidiary organization the Islamic Jihad of Palestine (PIJ) for the first time. That is, in the sense that westerners are being introduced to a new wave of sensationalist fervor by western media outlets: the fear of a global Jihadi terrorist fifth column— touching upon and reigniting the post-9/11 sentiments of many Americans.1

However, the politics behind the Islamic Resistance Movement are far more complex than what is currently being depicted. The Al-Aqsa Flood Operation conducted by Hamas on October 7 did not occur in a vacuum, nor was the 2001 designation of Hamas as an Islamic terrorist group a random occurrence. I believe it is crucial at this time to approach this subject with clarity, and to seek a historical and sociological approach in understanding the political ideology, strategy, and origins of Hamas.

Origins of the Islamic Resistance Movement

The Islamic Resistance Movement (Harakah al-Muqāwamah al-ʾIslāmiyyah, or more commonly known by the acronym Hamas) developed at the start of the First Intifada, amidst mass riots in the Gaza Strip in 1987, however the group’s political and intellectual genealogy extends much further as an off-shoot of the Palestinian chapter of the non-violent Sunni revivalist group Ikhwan al-Muslimoon (Muslim Brotherhood) established in 1945.2 Developing out of the milieu of Islamist social work, the modern organization of Hamas (that is in terms of its official distinctiveness from the Muslim Brotherhood), began with the establishment of the Islamic charity al-Mujamma al-Islami in 1973; its founders Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, Ibrahim al-Yazuri, Abd al-Aziz al-Rantisi, and Mahmoud al-Zahar, all being refugees from villages elsewhere in occupied Palestine residing in the Gaza Strip. Hamas’ origins within the Muslim Brotherhood become exceedingly prescient as it is important to note that Hamas is not merely a paramilitary organization, and in fact encompasses a vast social-sector categorically distinct from the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades (Hamas’ official military wing established in 1991). While visuals of armed militants in balaclavas and green headbands have certainly come to represent Hamas in its totality in the western mind, it is perhaps more difficult to imagine the reality of the Islamic Resistance Movement as a broad socio-political organization and grassroots movement within Palestinian politics, in which the average Hamas member is more likely to be a Gazan civilian wearing a suit-and-tie as opposed to military gear. Sara Roy (2011), the world’s leading academic expert on Gaza, aptly describes the West’s (and of course Israel’s) depiction of Hamas as a totally one-sided, propagandized, and reductive assessment:

As the representative of political Islam in Palestine, Hamas has had a long and contentious and, in its own way, remarkable trajectory. Typically, Hamas is mis-portrayed as an insular, one-dimensional entity dedicated solely to violence and to the destruction of the Jewish state. It has largely, if not entirely, been defined in terms of its terrorist attacks against Israel. Despite the existence of differentiated sectors within Hamas—social (including a nascent economic sphere), political, and military—they are all regarded as parts of the same apparatus of terror3

Roy’s expert investigation of Gazan civil society reveals a rarely seen perspective, that of Hamas as a genuine political organization encompassing a humanitarian social sector. Roy regards the Bush Administration’s November 2001 designation of Hamas as a terrorist group as a false-flag shaped by War on Terror hysteria, failing to differentiate between the ‘threat’ of Hamas’ militant brigades and its massive social-political sector (note: Hamas was originally designated as a foreign terrorist entity by President Clinton in 1995.) Roy writes, “a key component of this designation was the belief that Islamic social institutions were an integral part of Hamas’s terrorist infrastructure in Palestine. Both the U.S. government and U.S. media perceived the role of these institutions to be largely one of indoctrination and recruitment.”4

State Legitimacy and Regimes of Terror

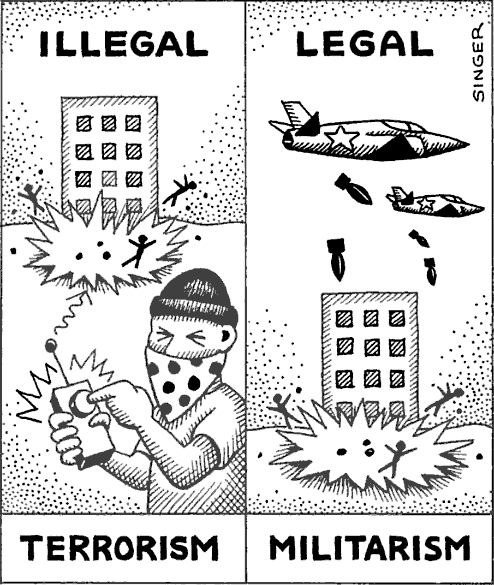

In understanding Hamas and the character of the Islamic Resistance Movement, we must first confront the real meaning and context of terrorism. We must ask ourselves, who, or what constitutes terrorism? Who, or what makes a state legitimate? To what extent can one differentiate between terror and military action? And who holds a monopoly on legal and illegal violence?

The term terrorism was first used to describe the period of violence that took place during the French Revolution and the 1793-1794 Reign of Terror, led by Maximilien Robespierre and his newly formed Comité de Salut Public (Committee of Public Safety), an organ of the French National Convention, serving as a public defense organization for the provisional government (including a literal policy of mass conscription—Levée en masse in French ) against the monarchist and oppositionist coalition. During this period in Revolutionary France, violence was enacted and directed against social and political forces that threatened the legitimacy of the French provisional government and its political program via the famed guillotine, an instrument formerly used to execute dissidents opposed to the French monarchy. In a curious twist of historical irony, the heavy blades of the enemy became the eminent symbol for the Revolution. It is perhaps fitting then that Hamas recycles the mechanical remnants of Israeli bombardments to engineer explosives for use in its resistance to the Israeli occupying forces and demand for Palestinian state-hood.

While today, it is easy to regard terrorism as renegade violence by individuals or groups of political actors, seeking to instill fear and disruption in the social sphere by means of indiscriminate violence, the term clearly originated in both revolutionary and state-enacted violence. Thus we are left with identifying what factors truly constitute a regime of terror.

The 2001 designation of Hamas and PIJ as terrorist groups on the same list containing organizations alleged to be responsible for the Twin Towers Attacks like Al-Qaeda, Lashkar-e-Taiba, and Jaish-e-Mohammed5 not only implicated the broad network of Islamic social and public institutions in Gaza, but also dozens of Muslim Brotherhood affiliated and even non-affiliated American Islamic charities, activist groups, and social work organizations providing much-needed relief and aid to Palestinians living in the Gaza Strip. In 2018 there was a continued attempt by the Trump Administration to designate the Muslim Brotherhood organization in its totality, including its affiliated international networks of charities and Islamic advocacy groups as a singular terrorist entity, established on the preceding logic of Bush’s War on Terror which indiscriminately regarded all Islamist and Islamic activity as a bedrock for Jihadi terrorism, with no differentiation between the religious ideologies of these groups.6

This however, is a simplistic view of Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood, failing to distinguish between the nuances of Sunni revivalist and Islamist social work and the perceived national security threat of Salafi Jihadism. The stratagem of Hamas’ military operations have historically made the distinction between civilian and military targets (unlike say the indiscriminate violence of ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and even the IDF)7, as seen at the height of their early activity between 1994 and 1996 whereby the utilization of suicide bombing campaigns were not wholesale, and were patently directed at Israeli military targets. Hassan Salameh, an actor behind Hamas’ suicide bombing operations, stated that the organization’s intentions in these operations were to seek revenge for the Mossad assassination of West Bank Hamas leader Yahya Abd-al-Latif Ayyash (an explosives engineer regarded as a martyr by then Palestinian National Authority President Yasser Arafat). The use of suicide bombing by Hamas operatives (however morally contentious)8 was neither a rejection of peace nor was it a cult worship of violence, rather it was explicitly political and conventional in nature. The Former Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres’ actions in executing Ayyash led to a direct and humiliating retribution, admonished and foretold by continued Israeli aggression in the Palestinian territories and rejection of peace deals in the wake of the Oslo Accords, as described by Israeli political scientist Ehud Sprinzak (1997):

In 1996, Peres experienced a dramatic decline in popularity because of the Hamas bombings. He could not admit that the risky order to execute [Ayyash] had precipitated the return of suicide terrorism. It was more expedient to tell Israelis that Hamas wished to bring his government down. Peres’ successor, Binyamin Nethanyahu, also needs to demonize Hamas. He does not truly believe in the Oslo peace process, [and] never has. Citing the public rhetoric of Hamas—which since 1988 has called for the destruction of Israel—helps him make his case9

It should be understood that the targeted violence towards Israeli military occupation by Hamas did not and does not appear at random, and is in fact a strategy of political retribution in response to ongoing Israeli aggression. Israeli officials like Peres and Nethanyahu regard this fact as a shameful secret, best kept from the Israeli public, as it is far easier to convince Israeli Jews that Hamas’ violent acts belong to a series of unwarranted terrorist plots than it is to recognize the political reality and inevitability of anti-colonial retribution. Through its public diplomacy strategy Hasbara, the Israeli state has an invested interest in producing the tactful rhetoric of wanton Islamist terror and concealing the Islamic Resistance Movement’s actual stated motives, all while manufacturing public consent towards Israeli military actions against Hamas, whose violence is deemed illegitimate compared to the legitimacy of the most moral army in the world. Sprinzak writes:

The dissection of the motivation for Hamas terrorism may seem talmudic to some, but it is important. The history of Hamas—in contrast to its stereotypical image in the western media—suggests that its opposition to the peace process has never led Hamas leaders to adopt a strategy of wholesale suicide bombing. Rather, suicide terrorism has been allowed by Hamas leaders as a measure of tactical revenge for humiliating Israeli actions

The view that Hamas is an organization that will resort to terrorism anywhere, anytime is simplistic. Why, for example, did Hamas leaders not resort to suicide bombings before April 1994; between August 1995 and February 1996; and between March 1996 and July 1997?10

Here we must note that Hamas has not officially claimed responsibility for a suicide bombing attack since at least the Kerem Shalom suicide bombing against an IDF military post in 200811, and possibly even earlier. Hamas’ hesitation to enact violence against Israeli civilians is also reflected in the 2017 charter, in which the Islamic Resistance Movement affirms the need to comply with the norms of international law within its liberation efforts.12 As we have so far established, there are no legal or rhetorical parameters by which we can regard Hamas’ violence as uniquely constituting terrorism as opposed to legitimate military action: a feature that is not exclusive to the Islamic Resistance Movement, but is also reflected in the militant operations undertaken by the secular PFLP and PLO at the height of their activities.

The Islamic Resistance Movement’s compliance with the standards of international law and pursuit of legal military action however, are in stark contrast to the actions taken by Zionist and Jewish fundamentalist para-military organizations during the land acquisition and state-building processes prior to the formal establishment of Israel. Founded in 1920, the Jewish para-military organization Haganah, carried out violent attacks against Palestinian Arabs in the British Mandate of Palestine for nearly three decades until its formal dissolution in 1948. While the organization claimed defense for native Yishuv (Ottoman Jewish) farmers and their kibbutzim against Arab aggression, these communal settlements were in fact a product of early Zionist land acquisition and take-over of Muslim Arab villages by European-Jewish settlers and Labor Zionists such as Arthur Ruppin and Yosef Baratz, hailing from Germany and Russia respectively. These early kibbutzim were instrumental in the total acquisition of Palestinian Arab land and the development of the Zionist project, as Ruppin would write, “the question was not whether group settlement was preferable to individual settlement; it was rather one of either group settlement or no settlement at all.”13 Ruppin would also be instrumental in the development of Zionist racial theory, in which he regarded Ashkenazi Jews as a kind of Jewish übermenschen, with Sephardic, Mizrahi, and Yemenite Jews as racial subclasses better utilized for menial labor, and unsurprisingly, Arabs as totally inferior and unfit to exist alongside Jews in a Jewish state.14

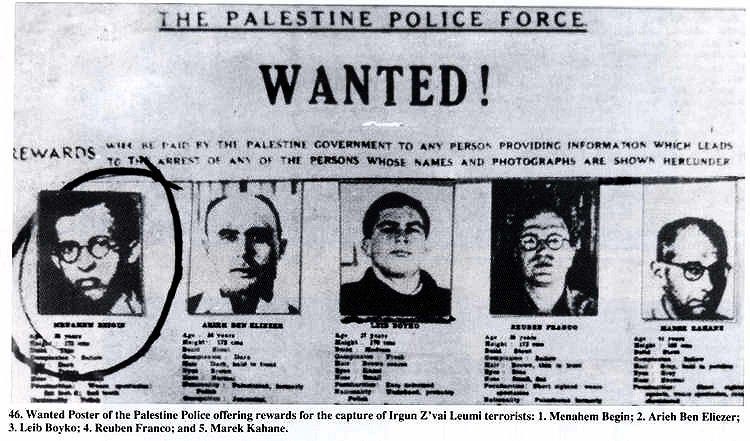

The ideologies of Ashkenazi Jewish supremacy and Jewish fundamentalism were central to the formations of radical terror groups split from the Haganah such as Irgun and its very own off-shoot Lehi, in which their terrorist campaigns against Palestinian Arab civilians led to a number of atrocities between the years 1931-1949 and 1940-1948 respectively. Central to the ideology of these Zionist para-military organizations, was the idea that terroristic violence was wholly justified in the pursuit of a Jewish state.15 The Irgun would go on to dedicate themselves to the same kind of bombing attacks and violent raids targeting civilians that Israel accuses the Islamic Resistance Movement of today. The 1946 King David Hotel bombing killed nearly 100 people including Palestinian Arabs and even a number of Jews. These atrocities ultimately culminated in the mass displacement and massacre of Arabs during the Nakba, in which the Irgun and Lehi massacred over 100 Palestinian Arabs in the Deir Yassin village and the forces of Haganah massacred over 200 Palestinian Arabs in the Tantura village, including women and children, in just a single day.16 Note that throughout World War II, Irgun and Lehi had also fought against British Forces in Mandatory Palestine, seeking to align with Nazi Germany, believing that the proposed Jewish state shared more in principle with the ideology of Hitler than it did with Britain, bringing into question and challenging the narrative of Israel’s creation as restorative justice for European Jews17. With the official establishment of Israel as a state in 1948, the core forces of Haganah, Irgun, and Lehi were integrated into the newly formed Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), giving rise to and legitimizing Israel’s ongoing regime of terror.

The Socio-Political Structure of Hamas

Hamas is not merely an organization comprised of gung-ho militants and suicide bombers as suggested by its prominent image in western media. The Islamic Resistance Movement is a vast network of religious socio-political organizations, coalitions, and social institutions, acting as a genuinely representative and democratic state-building alternative to Israeli apartheid, and a source for developing legal and social institutions alongside general public welfare in Palestine. It is the de-facto governing body of Gaza, and its legitimacy as a political organization is recognized and felt by the Palestinians living in Gaza, with its social work received by most, if not all Gazans. Hamas’ humble origins in Palestinian refugee camps are keenly reflected in its continued presence and communal work in the most destitute areas of the Gaza Strip. Hamas is responsible for the building and maintenance of mosques, madāris (Islamic schools), zakat committees, public schools, clinics, hospitals, nurseries, labor offices, and other civil institutions18—all of which are regarded as ‘Hamas strongholds’ and thus considered viable military targets by the criminal IDF.

Prior to Hamas’ militarization in the First Intifada, its parent charity organization al-Mujamma established social and communal programs in the poorest neighborhoods of Gaza. “In Khan Younis, for example, the Mujamma established a [free] medical clinic that was staffed by its own membership, set up a dental service in the nearby refugee camp, and ran a kindergarten.”19 With the official establishment and militarization of Hamas, the Islamic Resistance Movement provided massive financial assistance to orphans (many of them having lost their parents in Israeli bombardments), providing a monthly stipend of about $33 to thousands of individual orphans in the Gaza Strip, amounting to between $2-4 million spent on orphan support annually by 1995.20 By the mid-2000s, the House of Book and Sunnah (HBS), a Hamas-affiliated humanitarian organization, operated health clinics in the Khan Younis area charging as little as five Israeli Shekels (or $1.25) for patient visits and two Israeli Shekels (or $0.50) for medicines. The HBS also operated a full-time public school for grades six through twelve, and provided relief such as food, clothes, orphan support, and cash assistance for impoverished Gazans.21

The refusal of the international community and even some ‘pro-Palestine’ sympathizers to recognize Hamas as a legitimate socio-political organization representing 2.3 million Gazans, both politically and materially, can not pave the way to peace. The Zionist caricatures and comparisons of Hamas to ISIS reek of the same anti-Islamic hysteria that led to the surveillance, torture, and abuse of millions of Muslims in America’s War on Terror landscape. It is the same violation that regards all Islamic activity globally as belonging to a cabal of international terror. It is not merely an absurd comparison, but it is demonstrably false and fails to understand the Islamic Resistance Movement at its base. While I do not intend to discuss in depth, Hamas’ Islamist ideology (See: Roy for that discussion), the organization bares absolutely no similarity to ISIS or Al-Qaeda beyond a superficial commonality in religion. In fact it was Hamas and PIJ that defeated the ISIS and AQ forces in the Sinai, and ISIS itself had only ever attacked the Israeli border once in its career— and subsequently apologized for it.22 We can observe further distinction between Hamas and Salafi Jihadist groups in terms of Hamas’ ‘officialness’, and condemnation of terror, whereas groups such as ISIS lament in these actions— going as far as to claim responsibility for acts of terror perpetrated by unaffiliated individuals in the west. In the words of Sprinzak, “whether we like it or not, Hamas is a Palestinian fact of life. Those who demand the elimination of this organization as a pre-condition for peace are saying, in effect, that there will never be peace.”23

To put this into an American perspective, the designation of Hamas as a terrorist entity, is no different to say, if the Democratic Party or any other left-liberal organization after the 2020 BLM resistance and protests, or perhaps more recently the GOP after the events of the January 6 Capitol Hill Insurrection were to be designated as terrorist organizations. Should then every registered voter, canvasser, campaign organizer, or even sympathizer of either party be regarded as a non-civilian combatant or terrorist? Would we be morally obliged to bombard the schools where the children of these ‘terrorists’ attend? Are the clinics, hospitals, and government offices located in Democratic or Republican constituencies viable military targets? This is effectively how Israel and its western allies regard the Islamic Resistance Movement and its subsidiary organizations. When the IDF raids the homes of Hamas terrorists and bombards Hamas strongholds, they are in fact targeting the foundations of every-day Palestinian life. Where then, is the line drawn between ‘civilian’ and ‘soldier’? For Palestinians it seems this line was long ago erased, perhaps never having existed in the first place.

Beyond Partisanship

Another failing of western observers in understanding Hamas is the difficulty that these observers seemingly have in positioning the Islamic Resistance Movement politically. How, for example, can a conservative Islamist movement be revolutionary? As established, Hamas provides over two million Gazans with daily relief and financial support, effectively contributing to the imperative of Palestinian nation-building. Hamas’ vast social sector allows Palestinians living in the Gaza Strip to experience some semblance of a normal life, one in which they and their children can attend school, partake in sports and activities, and receive medical care— all under a sweeping blockade, constant bombardments, and a brutal occupation-apartheid system otherwise rendering daily survival an impossibility. Beyond providing social services and an alternative to starvation however, the Islamic Resistance Movement also provides Palestinians with a revolutionary framework for liberation.

Indeed, Hamas and PIJ are both conservative movements— in that the Islamic Resistance is conserving Palestinian culture, peoplehood, and the right to exist. Many leftists and liberals generally, and quite wrongly, presume that conservatism is the preservation of the status quo, to blindly preserve vague notions of tradition, and to manage social and political, and even structural change more cautiously than liberalism does— thus incapable of being revolutionary. In the face of total extermination and occupation however, the religious conservatism of the Islamic Resistance is quite simply, the conservation of a people and their traditions, in a landscape where liberalism is not only the dominant political ideology, but also entails normalization with and recognition of the Jewish nation-state, and placid acceptance of its political rituals and features. These political features include the ideals of liberalism already presently found in the Zionist entity: secular-modernity, citizenship, majoritarian democracy (which naturally favors European-origin Israeli Jews), and the sovereignty and rights of the individual. Like all revolutionary movements, Palestinian Islamism seeks to destroy the old and develop the new, firmly grounding its nation-building aspirations in a revolutionary Islamic framework.

Fathi al-Shaqaqi, founder of the Islamic Jihad of Palestine developing out of the more militant Qutbist elements of the Muslim Brotherhood, was deeply inspired by the Marxist ideologies of V.I. Lenin and Mao Zedong, and of course Sayyid Qutb, who himself developed a theory of Islamist vanguardism out of Lenin’s works. This engagement with Marxist theories of imperialism, capitalism, colonialism, and socialism shows us that the Islamic Resistance can not be neatly positioned into the categorical partisanship of western political ideology, be it ‘left’ or ‘right’, ‘radical’ or ‘conservative.’ These categorical poles of western partisanship, having developed out of the unique conditions of Revolutionary France and the European Enlightenment, can not be simply transposed onto the realpolitik of the Islamic Resistance. Hamas and PIJ thoroughly engage with Marxist and anti-colonial frameworks, not in spite of, but because of their conservative (or more accurately conservationist) Islamist ideology. It is from this we begin to understand that the Islamic Resistance is in fact an authentic reflection of Palestinian politics and more importantly, a reflection of Palestinian life. The pragmatic politics of Hamas and PIJ are unconstrained by the idealistic dogmas of leftism and rightism, and are instead developed in accordance to material needs and demands of Palestinian reality.

The dilemma of positioning the Islamic Resistance Movement in terms of political partisanship becomes all the more difficult when considering the already existing partisanship engrained in the foundations of the Israeli state apparatus. If the direction of ideology is positioned as either left or right, how then, do we contend with the contradictions between Israeli and Palestinian partisanship? The Israeli left which seeks to expand social welfare, democratic values, and civil rights arguably shares less in common with the Palestinian left than it does with the categorically right-wing Jewish fundamentalists and Israeli libertarians, who, despite their attempts at democratic backsliding which has produced friction between the ideological poles of Israeli civil society, also seek to preserve the interests and security of the Israeli state. The national interests of the Palestinian Islamist ‘right’ and secular left in the dismantling of the Jewish state pose an equal threat to the entire Israeli political spectrum, paradigmatically shifting ideological and political partisanship towards national conflict.

The IDF’s aforementioned predecessors, the Haganah, Irgun, Lehi, and Labor Zionist militias all constituted factions espousing both socialist and fascist beliefs, unified in their political and national interests in developing a Jewish state and the massacring of Palestinian Arabs as a means for land acquisition. The socialist Mapai (Worker’s Party of the Land of Israel) led by David Ben-Gurion worked in tandem with fascist and pro-Nazi Zionist militias in securing land for the development of the earliest kibbutz communes. Thus, it is only natural that a revolutionary and religious conservative movement would serve as the main conduit for military, social, political, and structural opposition to the Israeli state and its bi-partisan regime of terror, which is already (almost contradictorily) founded upon both leftist and fascist thought. The demands of Palestinian state-hood exist beyond the partisanship of liberal democratic ideals, which so far have only brought forth bloodshed and annihilation for Palestinian Arabs. The Palestinian Islamic Resistance, in order to be successful, seeks to build a nation in its own image, and not one of its European occupiers.

Erik Skare (2021) describes al-Shaqaqi as “as a remarkably prolific intellectual and ideologue with an oeuvre spanning from 1979 until his assassination on October 26, 1995.” Skare writes on the obscurity and neglect of Palestinian Islamist ideology by western observers, saying:

Little is nonetheless known about the actual political thought and ideology of the movement despite its relevance. While the literary works and speeches of al-Qaida, Taliban, Hezbollah, and the Islamic State (IS) have been translated and published for an English-speaking audience, the same cannot be said about PIJ. In fact, when analyzing political Islam, we often refer to Hassan al-Banna and Abul A‘la Maududi as its trailblazers, and Hassan al-Turabi, Rachid Ghannouchi, Yusuf al-Qaradawi, Muhammad Khatami, Sayyid Qutb, Ali Shariati, and Ayatollah Khomeini as its ideologues and intellectuals

While Fathi al-Shiqaqi argued that God predestined the victory of the Palestinians, this victory would also introduce independence for all states in the Global South under the shade of Western colonialism. While PIJ’s principal tool for Palestinian popular mobilization in the First Intifada was religious symbolism, its analysis of the conflict in the same period was, and still is, largely secular. While being one of the least compromising Palestinian factions regarding cease-fires with, and armed struggle against, Israel, it is also one of the most ardent proponents of dialogue and peaceful discussions in intra-Palestinian conflict24

Unlike secular organizations such as the PFLP and the PLO, the Islamic Resistance Movement is willing to engage with Marxist theories of liberation while also maintaining an Islamic critique of secular epistemology. In citing the works of Marx, Lenin, and Mao, al-Shaqaqi also utilized Shari’i principles in developing an Orthodox Islamic conception of the state, in which the modern nation-state with its rigid borders, secular-modernity, and blood and soil nationalism must be abolished to achieve a truly Islamic society, one that recognizes the total sovereignty of God as the defining factor of all social and historical development. This conception of history is rooted in of course, the Islamic occasionalism of Al-Ghazali, but also in the thought of Egyptian social reformer and Muslim Brotherhood founder Shaykh Hasan al-Banna, who wrote:

Internationalism, nationalism, socialism, capitalism, bolshevism, war, the distribution of wealth, the relation between producers and consumers, and whatever is related to these topics [...] which have occupied the leaders of nations and philosophers of society—all of these, we believe, Islam has penetrated to the core. Islam established for the world the system through which man can benefit from the good and avoid dangers and calamities

If the French Revolution decreed the rights of man and declared freedom, equality and brotherhood, and if the Russian revolution brought closer the classes and social justice for the people, the great Islamic Revolution decreed all that 1300 years before. It did not confine itself to philosophical theories but rather spread these principles through daily life, and added to them [the notions of the] divinity of mankind, and the perfectibility of his virtues and [the fulfilment of] his spiritual tendencies25

The Islamic Resistance Movement’s epistemology and engagement with revolutionary theory is derived from a systematic understanding of Islam, its jurisprudence, the teachings and meanings of the Qur’an, and the living practice of the Sunnah.26 This Islamic framework regards the issue of Palestine as not solely one of national liberation, but places it in the context of a greater civilizational struggle— not necessarily one of Islam vs the west, but Islam’s conception of retributive and restorative, and even divinely decreed justice, against an oppressive and global regime of Jahiliyyah (ignorance). Thus, Palestine becomes a struggle for the entirety of the Islamic ummah (nation), with the victory of the Islamic civilization being a promise from God, a prophecy which cements the morale behind the Islamic Resistance.

What we are witnessing with the militant actions taken by Hamas and PIJ in the Al-Aqsa Flood Operation, is a civilizational struggle which seeks to secure the continued existence of Palestinian peoplehood, not as isolate and disparate communities within one particular region, but as belonging to a broader Islamic Civilization— a consciousness that is currently surging through the Muslim World. In essence, the Islamic Resistance seeks to define itself on its own terms, as neither ‘left’ nor ‘right’, but as Palestinian people.

They [martyrs] are happy with [the blessings] which God has given them out of His bounty, and they are joyful [about those] who have not joined them yet and remained behind [but they will join them soon in Heaven]. And they will neither fear nor grieve. They are happy with God’s bounty and grace, and that God does not waste the rewards of the believers

Surah Ali-Imran [3:170-171]

Since the release of a statement on October 13, 2023 calling for world-wide protest by Khaled Mashal, the former chairman of Hamas’ politburo, numerous far-right commentators and media outlets have spread a series of misinformation campaigns, cultivating in the fear of a “Global Day of Jihad” resulting in the hate-fueled murder of a six-year old Palestinian child. See: Gilbert, David. (2023, October 13). “Rumors of a ‘Global Day of Jihad’ Have Unleashed a Dangerous Wave of Disinformation”. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/day-of-jihad-disinformation-israel-palestine/

Roy, Sara. (2011). Hamas and Civil Society in Gaza: Engaging the Islamist Social Sector. Princeton University Press. p. 19

Ibid, p. 1

Ibid

U.S. Department of State. Foreign Terrorist Organizations. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/foreign-terrorist-organizations/

U.S. Government Publishing Office. (July 11, 2018). The Muslim Brotherhood’s Global Threat. Retrieved from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115hhrg31367/html/CHRG-115hhrg31367.htm

In 1983, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Nethanyahu defended the killing of civilians as “an outcome of war, not terrorism” https://twitter.com/mohammed_hijab/status/1715315447157923973

For further discussion see “On Suicide Bombing” by Talal Asad (2007)

Sprinzak, Ehud. (October 27, 1997). “Learning to Live with Hamas.” The Washington Post National Weekly Edition.

Ibid

Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (April 19, 2008). Suicide bombing attack at Kerem Shalom, 13 soldiers wounded. Retrieved from https://www.gov.il/en/Departments/General/suicide-bombing-attack-at-kerem-shalom-13-soldiers-wounded

Middle East Eye. (2017). Hamas in 2017: The document in full. Retrieved from https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/hamas-2017-document-full

Rayman, Paula. (1981). The Kibbutz Community and Nation Building. Princeton University Press. p. 12

See: Morris-Reich, Amos. (2006). “Arthur Ruppin’s Concept of Race.” Israel Studies. p. 16 and Frantzman, Seth. (2014). “Israel’s Uncomfortable History of Racist Engineering”. The Forward.

Cleveland, William. L. (2004). A History of the Modern Middle East. p. 243

Al-Jazeera. (April 9, 2023). “The Deir Yassin massacre: Why it still matters 75 years later.” Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/4/9/the-deir-yassin-massacre-why-it-still-matters-75-years-later

Sofer, Sasson. (1998). Zionism and the Foundation of Israeli Diplomacy. Hebrew University of Jerusalem. pp. 253-254

Paraphrased from Sprinzak (1997)

Roy, Sara. (2011). Hamas and Civil Society in Gaza: Engaging the Islamist Social Sector. Princeton University Press. p. 73

Ibid, p. 80

Ibid, pp. 103-104

Gross, Judah Ari. (April 24, 2017). “Ex-defense minister says IS ‘apologized’ to Israel for November clash.” The Times of Israel. Retrieved from https://www.timesofisrael.com/ex-defense-minister-says-is-apologized-to-israel-for-november-clash/

Sprinzak, Ehud. (October 27, 1997). “Learning to Live with Hamas.” The Washington Post National Weekly Edition.

Skare, Eric. (2021). Palestinian Islamic Jihad: Islamist Writings on Resistance and Religion. I.B. Taurus. pp. 1-2

Michell, Richard. P. (1993). The Society of the Muslim Brothers. Oxford University Press. p. 233

Skare, Eric. (2021). Palestinian Islamic Jihad: Islamist Writings on Resistance and Religion. I.B. Taurus. p. 10